Who owns the copyright in the screenplay of a film if the author has been commissioned by the producer of the film to write the screenplay? Is it the producer of the film or the author of the screenplay?

Interesting questions, right?

Recently, Honourable Delhi High Court delivered an iconic judgment (in the case of RDB AND CO. HUF vs. HARPERCOLLINS PUBLISHERS INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED, 2023) on this issue. The decision made a well-deserved headline as the creator in question was the iconic film director Satyajit Ray! If you are a screenwriter/filmmaker and the quote of this judgment has yet to reach your WhatsApp status, then you are definitely sleeping under the rock! The landmark judgment of recent times has the potential to turn the tide on how our film industry is operating. So, without further ado, let me decode this judgment in the simplest term, along with its impact on you. If you are a screenwriter or filmmaker, please keep everything aside, read this article, and share it with your folk.

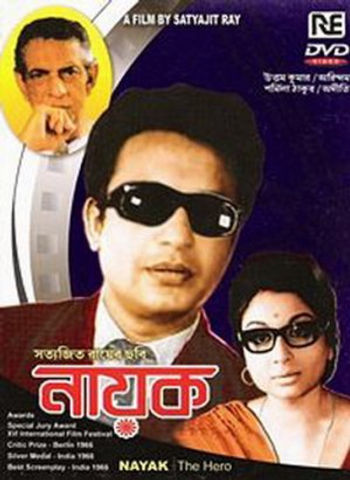

Let’s start with a brief fact, Satyajit Ray was commissioned by the Producer (R.D. Bansal) to write the screenplay of and direct the film ―Nayak. Satyajit Ray wrote the screenplay and also directed the film. In 2018, Mr. Bhaskar Chattopadhyay novelized the screenplay of ―Nayak after getting permission from Late author Ray’s legal heirs. The Production house sued Mr. Chattopadhyay for copyright infringement for using their script without their consent.

The Producer side relied on Section 17 of the Copyright Act 1957 (Act), under which the Producer commissioned the screenplay. Hence, they are the owner of the copyright of the screenplay. Whereas, Mr. Chattopadhyay’s side argued that the right of the Producer is limited to the copyright of the cinematographic film and the right of underlying work (screenplay in the present case) is vest in the author of the script (i.e., Satyajit Ray). Hence, they rightfully took the permission from the legal heirs of Ray to novelize the script.

It has been a common understanding in the industry that if a producer commissions the project (even if the agreement is not signed), the producer deems to be the owner of the entire script. The producer side always relies on Section 17 of the Act. I researched the existing case laws regarding the analysis of Section 17 from the screenplay’s point of view. However, I could not find a clear-cut comment at this point. In this judgment, the honorable court has analyzed Section 17 in length and put rest to all the conflicting arguments.

Present judgment has served this gap well. The Court held that the opening words of Section 17 lay down a clear principle that the author of a work is its first copyright owner. However, there are exceptions outlined in the Copyright Act and within the proviso to Section 17 itself. The proviso consisted of four clauses labeled (a), (b), (c), and (d). Clause (a) pertains to works created by authors employed by newspapers, magazines, or similar periodical proprietors, which doesn’t apply in this case. Clause (b) covers photographs, paintings, portraits, engravings, or cinematograph films created at someone’s request. But it doesn’t encompass screenplays. The mention of a “cinematograph film” in this clause only applies when one person produces a film on behalf of another person. Clearly, this situation does not pertain to the matter at hand, which is related to the “Screenplay.”

Clause (c) of Section 17 addresses works created during an author’s employment under a contract of service or apprenticeship. However, this clause is also irrelevant in this context for two significant reasons. First, the principle of noscitur a sociis applies, meaning that the meaning of a word should be understood in relation to the words accompanying it. In this case, the term “service” in clause (c) of the proviso to Section 17 must be interpreted as service akin to apprenticeship. Apprenticeship involves a master-servant relationship and the principle of hire, which does not apply here. Second, the use of the phrase “contract of service,” particularly in conjunction with “apprenticeship,” within clause (c) of the proviso to Section 17 clarifies that the clause does not cover cases where two parties enter into a contract as equals, where one person provides a service to another, such as the situation at handwriting and directing a film.

Hence, the Court concluded that Satyajit Ray is the author and owner of the screenplay of the film Nayak. He has given the license to the producer to adapt the screenplay into the film.

To summarize, according to the judgment, the producer retains ownership of the film. Consequently, if a screenwriter is working on the script as an independent contractor, the provisos of Section 17 do not apply. Therefore, the screenwriter remains the author and rightful owner of the screenplay. This ruling effectively resolves any lingering misunderstandings regarding commissioned work scripts. Additionally, Section 13 (4) of the Copyright Act solidifies this position. It states that the copyright in a cinematograph film or sound recording does not affect the separate copyright of any work, or a significant portion thereof, incorporated within the film or sound recording.

Consequently, it is of utmost importance for authors to fully understand their rights and actively negotiate contractual agreements that reflect their interests. If a producer seeks to obtain complete ownership of the script, it becomes essential to draft a comprehensive and all-inclusive agreement that explicitly addresses the various aspects of copyright. Such an agreement should encompass the transfer of each right separately, compensation terms for each right, credit provisions, and any other relevant considerations. Both parties, the author and the producer, should engage in open and transparent negotiations to ensure that their respective needs and expectations are met. By actively participating in the negotiation process and signing a well-defined agreement, authors can assert their creative rights, protect their intellectual property, and establish a fair and mutually beneficial working relationship with the producer. It is through this proactive approach that authors can confidently navigate the intricacies of the industry, preserve their artistic integrity, and secure their rightful position as respected contributors to the filmmaking process. Definitely, this judgment shall act as a lighthouse in the same!

In case you have a particular query regarding your specific case (with reference to this judgment), feel free to book a legal consultation session by emailing attorneyforcreators@gmail.com.